Understanding Stripe's Latest $6.5B Fundraise

On Employee Compensation, RSUs, Taxes and Triggers

This is a weekly newsletter about the business of the technology industry. To receive Tanay’s Newsletter in your inbox, subscribe here for free:

Hi friends,

It’s been a crazy few weeks for the technology ecosystem – I hope everyone is hanging in there and their deposits are safe and sound. Enough has been written about SVB and its implications, so I'll focus on another topic this week.

A few days ago Stripe announced that it raised over $6.5 billion in Series I funding to value the company at $50 billion (a down round).

The unique thing about this raise was that Stripe made it clear that “it does not need this capital to run its business” and the purpose of the raise was to “provide liquidity to current and former employees”.

So let’s discuss what’s going on here, starting with a quick look at some of the basics. I’ll cover:

Startups and their Use of Options

How RSUs work and Single and Double trigger RSUs

Usage of RSUs at Public and Private Companies

What Happened at Stripe

I. Startups and Options

In technology, it’s pretty standard for companies to provide compensation to employees in the form of equity.

At startups, usually, that equity is granted in the form of options, which comes in one of two types1:

Incentive Stock Options

Non-Qualified Stock Options

Both of them would give the holder the option but not the obligation to purchase shares in the specific company. Employees only end up paying taxes on these options when they actually exercise their right (or later) as opposed to doing it when they receive the options.

However, as a startup grows, two things happen:

The price at which options are granted and as a result, the cost to exercise these options may grow prohibitively large. For example, if a private startup is worth $1B, and it issued someone 40K options with a strike price of $10/share. Now, say they leave 4 years later. If the company is not public yet, that person will have to shell out $400K to exercise these options, which is infeasible for many.

As the potential upside reduces, more options may be needed to attract talent which would increase dilution.

How might a startup combat this? Through RSUs.

II. RSUs

RSUs, which stands for Restricted Stock Units, is essentially a promise from the employer to give you units of stock in the company on a certain schedule if certain criteria are met.

Compared to options, RSUs have a few benefits:

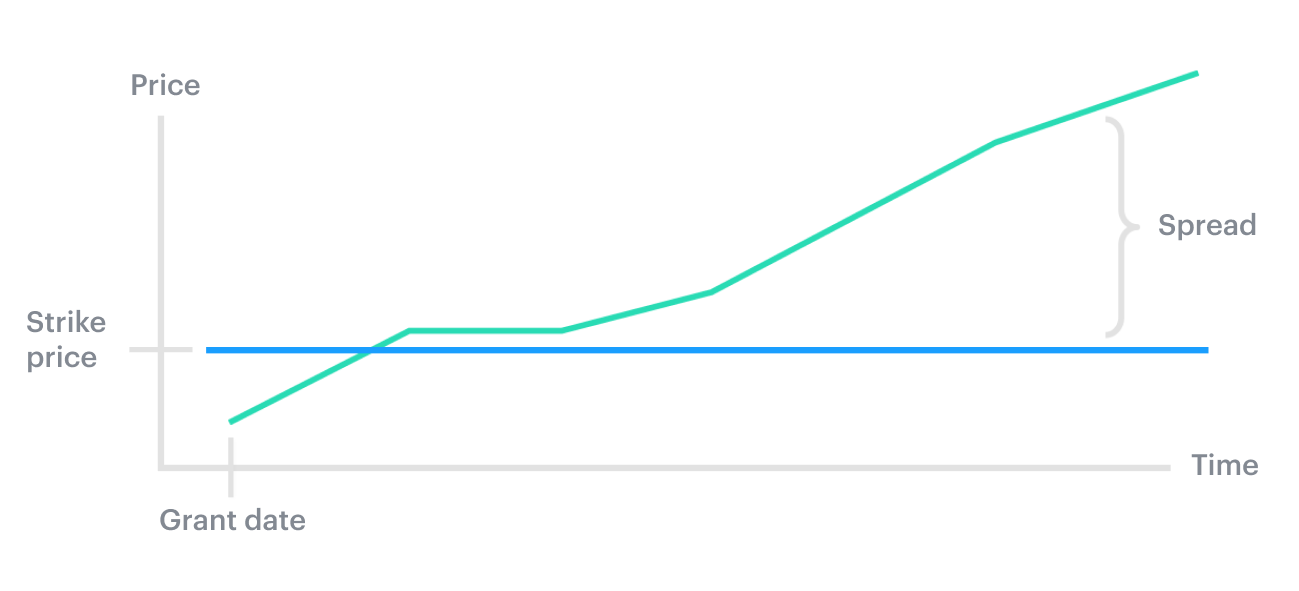

No “cost” to exercise them (you can think of it as an option given to someone with a $0 exercise price)

Safer in the case of downside scenarios (due to there not being a strike price)

Usually easier to understand the grant value at the offer date and in various scenarios

Less dilution to the company compared to a similarly valued option grant (i.e, giving someone 20K RSUs worth $20/share vs 60K options at a strike price of $17.5 may be viewed similarly by employees, but result in less dilution)

Tax Treatment

When RSUs are granted, no taxes are due. However, when RSUs are vested by the employee, the value of RSUs is treated as income to the employee as soon as they are received by the employee at the Fair Market Value of the RSU.

In essence, people owe taxes when they receive these stocks at the value on that date when they vest them.

Triggers and Types of RSUs

Two types of triggers or criteria usually affect the vesting of these RSUs:

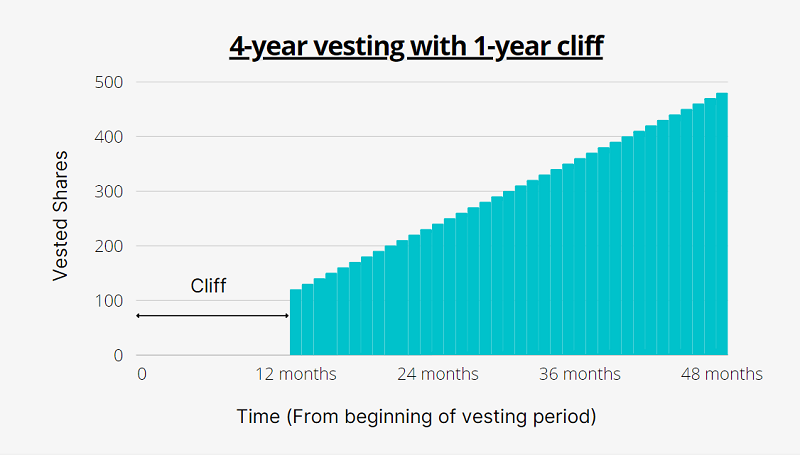

A time-based trigger – i.e., you being employed on certain dates to vest the RSUs as per a vesting schedule (1-year cliff, X-year vesting, etc)

A milestone or performance trigger – usually tied to a company going public or being acquired or for senior leadership around hitting certain targets.

Generally, RSUs almost always have a time-based trigger, and so the two common types of RSUs in practice are:

Single Trigger RSUs: Usually vest dependent only on a timing schedule/trigger, as in the illustration below.

Double Trigger RSUs: Usually vest dependent on both a timing schedule/trigger and a certain performance trigger (usually a liquidation milestone being hit such as IPO/Acquisition, etc). One important note about these is that to delay the taxation event they must have an expiration date (usually 5-7 years out) to give a “substantial risk of forfeiture” for tax purposes (i.e., there must be a meaningful risk that the performance clause may not be met during the term).

III. Usage of RSUs

Public Companies generally use Single-Trigger RSUs

In the case of public companies, the usage of RSUs is pretty straightforward. Since the company is public and the stock is liquid, a standard single-trigger RSU based on some time period is sufficient.

When someone joins Google, Google may offer them 2000 RSUs vesting over 4 years, with a quarterly vesting schedule (worth $200K at $100 per share). These are single-trigger RSUs, in that the employees vest them on one trigger – time i.e. being employed at that date.

So every quarter, the person receives 125 stock units, and is responsible for tax on those at the price at vest (i.e., maybe $80 or $120), but can sell a portion of them to cover the tax given they are liquid.2

Private Companies generally shift to Double-Trigger RSUs from Options

As private companies grow, issuing RSUs instead of options has several benefits as discussed above. In fact, as the below graphic from Carta show, companies tend to move towards RSUs post the unicorn stage.

But they generally can’t use single-trigger RSUs. Why? When the employee vests shares every quarter/year, they owe taxes on that vested amount, but since the company is private, they cannot sell some of the shares to pay taxes and so may be unable to pay the taxes on it.

For example, let’s say Stripe gave someone 50,000 RSUs (valued at $10 per share when they joined) with a 4-year vesting and 1-year cliff. A year later, when they vested 12500 of them, the FMV of each share is $20, meaning they vesting $250K and now owe taxes on $250K. How exactly are they expected to pay that given Stripe stock isn’t liquid?

For this reason, startups that move from options to RSUs while private typically use double-trigger RSUs of the following form:

The first is a standard time-based one (e.g., vesting quarterly over 4 years with a 1-year cliff)

The second is tied to a liquidation event for the company (IPO / Acquisition)

This means, that the RSUs officially vest only when both triggers are hit, so employees face the tax bill only upon a liquidation event when they can sell a portion of the RSUs to cover the taxes on it.

The catch however is that double-trigger RSUs require an expiration period from a regulatory perspective. Usually, that period is 7 years. If the two conditions above are not met within that time frame, they expire worthless.

If you don’t yet receive Tanay's newsletter in your email inbox, please join the 7,000+ subscribers who do:

IV. What Happened At Stripe?

Starting in ~2016, Stripe starts to offer new employees RSUs instead of options. It was already valued at >$5B at this time.

These RSUs are double-trigger RSUs, with standard time-vesting schedules and performance-based vesting (IPO/Acquisition) with expiration in 7 years.

Now, we’re close to the 7-year mark where the initial RSU grants of these current/former employees would expire because the second trigger (go public/be acquired) was not hit, through no fault of their own.

With IPO windows shut Stripe has two options: (1) let these RSUs expire, meaning many employees’ grants in theory worth millions expire worthless, or (2) remove the second trigger of the RSUs (IPO/Acquisition) but resulting in these employees facing huge tax bills since they vest the RSUs now.

Stripe chose option (2), raising $6.5B to help employees who face these tax bills. The board can waive the second trigger on the RSUs so that all those RSUs vest now since the time conditions have been met. This means that employees with vested RSUs face a huge tax bill. But given that Stripe has raised the money, it can help employees cover taxes by basically either providing some form of loan to them and/or buying back a portion of their now vested RSUs so that they have the capital to cover their tax burden.

In many ways, this funding round isn’t even a primary funding round at all, but instead somewhat of a secondary sale, where employees with be able to sell their shares back to the company at somewhere around the same price that investors as part of this round invested at.

I expect the net dilution as a result of this round to be 0-2%, depending on whether Stripe ends up loaning money to employees to cover taxes, or requires them to sell their stock back to do so.

Also, Stripe management should be applauded for this. While they potentially did make a mistake by not going public in 2021, they did not have to do this for employees. Sure, it would have been an extremely rude move to leave current and former relatively-early employees in the dust, but not many companies that face this situation are even in the position to do this. Foursquare, for example, lets employees’ RSUs expire when in this same situation.

Stripe was in a relatively strong position given it despite its recent issues it’s still a Silicon Valley darling with investor demand, and was able to do this for its employees who had rightly earned their stock through their hard work, as CEO Patrick Collison noted:

Over the last 12 years, current and former Stripes have helped build foundational economic infrastructure for millions of businesses around the world, and this transaction gives them the opportunity to access the value they’ve helped create.

As companies are staying private for longer and longer, and many of them shifted to RSUs post-unicorn stage, there may be other companies facing a similar dilemma soon, especially if IPO markets remain shut for a lot longer.

V. Additional Reading

My prior piece on Understanding some company’s use of one-year equity grants

Stripe’s official fundraising announcement

The Information piece on Stripe’s Dilemmas

Thanks for reading! If you liked this post, give it a heart up above to help others find it or share it with your friends.

If you have any comments or thoughts, feel free to tweet at me.

If you’re not a subscriber, you can subscribe for free below. I write about things related to technology and business once a week on Mondays.

They have some interesting differences in terms of tax liability, and who they can be granted to, but that’s a topic for a different day.

In practice, public companies can directly withhold RSUs and sell them to cover the employee’s taxes and give them the post-tax units.

Love this simple explanation. RSUs and stock options have always boggled my mind a bit and this really helps clarify some of those concepts 👏