Overbuilding in AI: A Modern Twist on an Old Tale

On overbuilding, demand signals and prior infrastructure buildouts

This is a weekly newsletter about the business of the technology industry. To receive Tanay’s Newsletter in your inbox, subscribe here for free:

Hi friends,

Recent earnings calls from the big tech companies reaffirmed their commitment to pouring massive amounts of capital into AI-related infrastructure. In this piece, I’ll explore the overbuilding in AI and how it echoes past investment booms.

The Overbuilding in AI

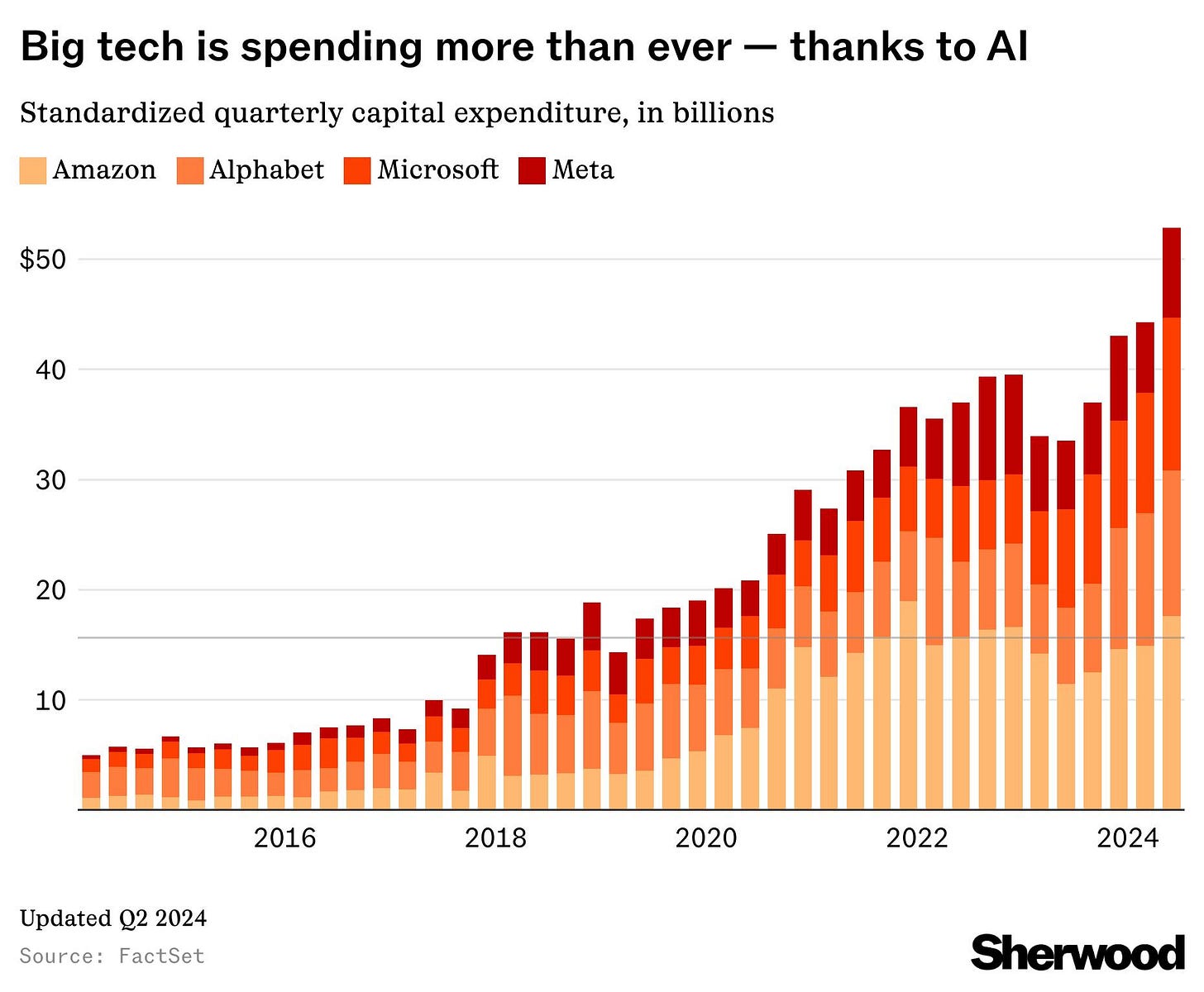

In their latest earnings calls, Google, Amazon, Meta, and Microsoft all shared a common message—continuing to ramp up their capital expenditures (capex) for AI infrastructure through 2025. The numbers are staggering: over $50 billion per quarter in aggregate capex by Q4 this year.

A common theme across these calls was the acknowledgment of potential overbuilding. Yet, the consensus was clear: the risk of underinvesting is far scarier than over investing.

Mark Zuckerberg noted in a recent interview with Bloomberg:

"I think that there's a meaningful chance that a lot of the companies are over-building now, and that you'll look back and you're like, 'oh, we maybe all spent some number of billions of dollars more than we had to … On the flip side, I actually think all the companies that are investing are making a rational decision, because the downside of being behind is that you're out of position for like the most important technology for the next 10 to 15 years."

Sundar Pichai echoed a similar sentiment in Google’s earnings call:

And in technology, when you are going through these transitions, aggressively investing upfront in a defining category, particularly in an area, which in a leveraged way, cuts across all our core areas, our products, including Search, YouTube and Other Services as well as fuels growth in Cloud and supports the innovative long-term bets and Other Bets. It is definitely something that for us makes sense to lean in.

The one way I think about it is when you go through a curve like this, the risk of underinvesting is dramatically greater than the risk of overinvesting for us here.But I think not investing to be at the front here, I think, definitely has much more significant downsides.

Overbuilding in the Past

This isn’t the first time we’ve seen a massive infrastructure buildout fueled by the fear of missing out. History is full of examples1—from canals to railways to telecom—where sudden investment surges led to both innovation and excess.

In the case of canals in the late 18th century, a significant number of new companies popped up, raising capital from the speculative public to build out the infrastructure.

Between the late 18th century and 1824, more than 60 canal companies were created, raising more than £12 million of new capital, equivalent to some $12 billion in today’s money. Demand for canal shares was so great that capital was widely obtained from public subscription on an unprecedented scale.

The telecom buildout we saw in the 2000s dwarfs even what we’re seeing in AI today, where almost $250B in capex was spent globally. Eventually this overbuilding resulted a glut of unused capacity, culminating in significant financial losses when the dot-com bubble burst.

Massive amounts of capital flowed into building both fibre optic and wireless networks to support the expected growth of a ‘connected world’, a phenomenon that the Internet was rightly expected to help materialise. Much of the capital in this case was diverted into the hands of governments in the form of wireless licence auction proceeds. An auction of third generation (3g) mobile phone licences in the UK and Europe resulted in $150bn being paid to various European governments in auction proceeds, simply for the right to operate. The same amount again was raised to build the 3g infrastructure before the licences could be used and any revenue earned. Total global capital expenditure for the telecoms sector in 2000 alone was $243bn, a figure two and a half times greater than that invested five years previously. Within this figure the largest elements were Internet-related, either for broadband access, optical networking or wireless infrastructure.

A similar phenomenon occurred in railways where there was a large increase in the capital flowing into these companies (and subsequently invested by these companies), following the “mania” and speculation, as evident in te chart below on British Railways.

If you don’t yet receive Tanay's newsletter in your email inbox, please join the 9,000+ subscribers who do:

What’s different this time?

While history rhymes, today’s AI boom does have some unique characteristics.

I. Strong Demand Signals

One key difference is the presence of stronger demand signals today. Unlike past cycles, where infrastructure was built on the hope and expectation that demand would follow, big tech companies are seeing real, tangible demand driving their AI investments.

Microsoft, for example, highlighted how Azure AI’s growth is leading their cloud business and that they are seeing more demand:

Azure AI growth, that's the first place we look at. That then drives bulk of the capex spend, basically, that's the demand signal because you got to remember, even in the capital spend, there is land and there is data center build, but 60-plus percent is the kit, that only will be bought for inferencing and everything else if there is demand signal, right? So, that's, I think, the key way to think about capital cycle even.

To meet the growing demand signal for our AI and cloud products, we will scale our infrastructure investments with FY '25 capital expenditures expected to be higher than FY '24. As a reminder, these expenditures are dependent on demand signals and adoption of our services that will be managed through the year.

Amazon echoed this:

Looking ahead to the rest of 2024, we expect capital investments to be higher in the second half of the year. The majority of the spend will be to support the growing need for AWS infrastructure as we continue to see strong demand in both generative AI and our non-generative AI workloads.

But it’s not all certain. Meta, for instance, doesn’t expect its GenAI products to drive revenue meaningfully in the near term:

We don't expect our GenAI products to be a meaningful driver of revenue in 2024. But we do expect that they're going to open up new revenue opportunities over time that will enable us to generate a solid return off of our investment

II. Infrastructure Flexibility

Another difference is the flexibility of today’s infrastructure—it has a long useful life, can be repurposed in various ways, and a portion of the spending can be aligned with actual demand.

Sundar Pichai noted:

Even in scenarios where if it turns out we are overinvesting, these are infrastructure which are widely useful for us, they have long useful lives, and we can apply it across and we can work through that.

Satya Nadella also called out the added flexbility of spending the bulk of the capital only when needed.

The asset, as Amy said, is a long-term asset, which is land and the data center, which, by the way, we don't even construct things fully, we can even have things which are semi-constructed, we call coal shelves, and so on. So, we know how to manage our capex spend to build out a long-term asset and a lot of the hydration of the kit happens when we have the demand signal.

III. Concentration and Centralization

In the past, overbuilding was often driven by a swarm of small companies and speculative investors, leading to fragmented, inefficient markets. The railway boom, for instance, saw numerous small companies competing for routes, resulting in duplication and financial disaster when the expected profits didn’t pan out.

Today, while we’ve seen a flurry of new startups and significant venture capital investments—around $20 billion per quarter in AI—the landscape is different. Unlike those earlier periods, the bulk of AI infrastructure investment is concentrated in the hands of just five to seven major players. Sure, there’s still speculation, especially among publicly traded AI companies, but it hasn’t reached the fever pitch of past booms.

What’s particularly interesting is that even the most promising AI startups often end up being financed by these larger tech giants at some point in their journey, as highlighted below in the chart by

byThis centralization marks a shift from the more speculative, decentralized overbuilding of the past. The current cycle is largely driven by the free cash flow and profits of these big tech companies, which helps mitigate some of the risks associated with overbuilding. At the very least, it means that speculative individual investors aren’t as directly exposed to the potential fallout if things don’t go as planned.

Closing Thoughts

The AI boom bears striking similarities to past episodes of overbuilding—massive capital expenditures and the looming threat of overcapacity. But this time around, strong demand signals and adaptable infrastructure could lead to a different outcome. That said, history still has valuable lessons to offer. Overbuilding, even when driven by real demand, comes with significant risks. The big question is whether the demand for AI will keep pace with this rapid expansion, or if, like in previous cycles, we’ll see supply outstrip demand, and by how much.

All quotes and charts in this section come from Engines that Move Markets by Alasdair Nairn