Understanding the Instant-Delivery Phenomenon

Can the likes of Gorillas, Fridge No More and 1520 Achieve Profitability?

Hi friends!

Many major cities have seen an influx of hyperlocal delivery apps, which promise groceries and convenience type products delivered to your doorstep in 15 minutes.

This week, I’m going to go into this model in more depth. But first, it’s worth touching on the typical “marketplace” model followed by DoorDash Convenience / Instacart and in some sense Amazon for grocery and convenience delivery:

Customers placed orders to items from a specific third-party store, and then a gig worker go to that store and purchase those items, before delivering it to the customer, typically in a 1 to 2-hour window.

With that out of the way, let’s talk about the Instant-Delivery Apps. I’ll go into:

An overview of the space

The vertically integrated approach and the commonalities they have

The business model and path to profitability as well as ways they might improve margins.

1/ Overview

There is currently a major landgrab for market share going on in many geographies in this instant-delivery space.

In NYC where I live, there are at least five apps that I can think off of the top of my head that offer ~15-20-minute delivery, along with arguably the pioneer in the space GoPuff (over $3.4B raised) which offers ~30-45 minute delivery:

FridgeNoMore which has raised $17M

1520 which has raised $8M

Jokr which has raised $170M

Buyk which has raised $46M

Gorillas which has raised $1.3B

This is by no means an American phenomenon.

Gorillas (EU HQed) operates in France, Germany, UK, Netherlands, Italy and Spain

Jokr operates across Brazil, Mexico, Colombia and Peru in addition to parts of Europe

Samokat (which Buyk is an offshoot of) and Yandex’s Lavka operate in Russia in this space

And there’s a whole host of others including Getir, Dija and Wizy in Europe

2/ Vertically Integrated Approach

While the specifics might differ slightly, most of the instant-delivery apps are vertically integrated and tend to have the following approach:

A. Dark Stores / Fulfillment Centers

Instant-Delivery Apps operate their own dark stores / fulfillment centers, typically one per neighborhood they operate in. Since these are not meant for consumers, space can be used more efficiently and typically the cost to operate these (at scale) as a percent of revenue is lower than rent space for grocery stores.

Once a consumer places their order, they are fulfilled at the corresponding fulfillment center by workers (“pickers”), and delivered by riders typically on bikes.

We are super-efficient. Don't forget about the fact that traditional grocery retail chains invest a lot in their spaces. We have considerably lower rents and small spaces, so we save a lot on that - 1520 Cofounder Maria Daniltceva

GoPuff for example operates over 500 micro-fulfillment centers.

B. Limited SKUs

A typical grocery store might carry ~15K SKUs. Meanwhile, the instant-delivery platforms, given their micro-fulfillment hubs, tend to carry a more limited selection today, though they are constantly expanding them.

In general, most of them carry 500-2000 SKUs currently, though with aims of expanding them to the 3000-5000 range.

Our dark stores are between 1,500 and 2,000 square feet. For now we have around 1,500 SKUs, and we are working on improving that. Our target is at some point to have 3,000 SKUs - 1520 Cofounder Maria Daniltceva

That selection is split typically between dairy and produce type items (which are higher frequency) as well as the more common convenience type items.

C. Neighborhood as the atomic unit

In the days of rideshare and food delivery, typically expansion by these companies happened on a city-by-city level, with the service available to most of a city after launch.

For instant-delivery startups, the neighborhood is the key atomic unit. Each micro-fulfillment center can serve a delivery radius of essentially 1-1.5 miles given the delivery windows. So, it’s not uncommon that while some of these startups operate in 20 cities, that within each of those cities, it’s only available in 10-15% of that city, based on the delivery zones of the fulfillment centers in that city.

It is very possible that given density and other factors, it might only make sense for these services to operate in specific portions of cities (or have longer delivery windows for other neighborhoods).

D. Employee Approach

Interestingly, many of the companies have taken the approach of hiring riders and other workers as part-time or full-time employees with benefits, rather than the gig worker model which is commonplace is food delivery and ridesharing.

Some of it might be down to the current environment with the backlash faced by the ridesharing and delivery companies for their gig worker practices. But arguably this can help better control logistics and operations early on and ensure adequate supply of riders to deliver orders in the required timeframes and offer a better customer experience.

E. Integrated Software and IT

These apps tend to have well integrated software and IT systems which are able to effectively track inventory in their fulfillment centers.

This is important and a differentiator from the third-party platforms which tend to not have real-time information on inventory and product selection leading to often relying on substitutions and replacements as part of the ordering process.

Additionally, since these apps control the customer experience and the inventory, they are able to have tighter feedback loops to change inventory ordering or even re-rank items on the fly in the app based on available inventory.

If you don’t yet receive Tanay's newsletter in your email inbox, please join the 3,000+ subscribers who do:

3/ Business Model and Profitability

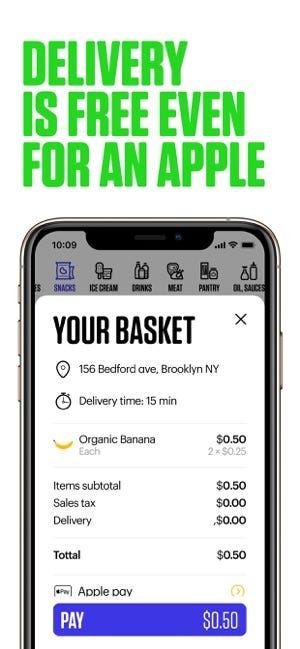

While the exact fee structures vary, today many of the instant-delivery apps have no fees and no-order requirements. The few that do have fees also tend to only have fees on smaller orders.

A. So how do they make money?

The primary revenue source is the price difference between what they purchase the inventory for and what they sell it to customers for i.e., the markups of goods.

The business model is more similar to that of the typical grocery store and supermarket than that of the 3rd party platforms like Doordash and Instacart.

It should be noted too, that since these instant-delivery apps purchase inventory upfront, the full value of their order is essentially “revenue” whereas for Doordash et al, only their take rate is considered revenue, and the full value of their order is GMV.

Some of them also charge delivery fees on certain orders, and so those fees are another source of revenue.

B. Are they profitable?

While we don’t know too much about the economics yet, The Information recently reported that these companies are unsurprisingly losing money.

But some are sustaining significant losses on each order. Jokr, a New York–based startup that launched its grocery-delivery services in 10 cities globally earlier this year, lost $13.6 million on just $1.7 million in revenue as of the end of July, according to internal data viewed by The Information.

But that isn’t the right thing to necessarily consider, since these companies are heavily investing in growth in new markets.

The more important thing to look at is the unit economics on transactions and what those could look like over time.

In addition, since the neighborhood is the atomic unit for these, it’s interesting to consider whether any neighborhoods have gotten to profitability, since at any given time, given the mix of neighborhoods and investments in new ones, the aggregate company could be unprofitable even if the model works. And there are some signs this is the case even at the entire country level.

Getir, for example, says it is profitable in its home market of Turkey where it has been since 2015. (via Sifted)

Some of Jokr’s older warehouses in Latin American cities have recently become “operationally profitable,” Wenzel added, meaning they were making money in the specific neighborhoods they serviced. (via The Information)

C. Economics compared to Grocery Stores

One exercise that is useful is to consider how the economics might look like compared to grocery stores, which in some sense are a better proxy for the model than Doordash et al.

Typical grocery stores have ~30% gross margins and 2-5% net profit margins, after considering costs such as labour and rent, as below.

Let’s see what it may look like for an instant-delivery app.

Gross Margins: In the case of instant-delivery apps, since they can charge a slight premium on prices given the convenience, they might be able to have slightly higher pricing (and so higher gross margins) in the long-term. However, today they don’t have scale and so don’t get the same wholesale terms and so probably have slightly lower gross margins.

Rent: Given the dark stores can be more space efficient since they aren’t met for customers to shop in, instant-delivery apps will probably have lower rent as a percent of revenue over time than grocery stores.

Picking costs / labour: While supermarkets need to have labour in-store to help customers and stock goods, instant-delivery apps need to have even more so because they are also doing the “shopping” on behalf of the users. Because of this, it’s likely that instant-delivery apps will have higher in-store labor costs as a percent of revenue. However, given the smaller sized fulfilment centers with more limited SKUs and use of technology, they may be able to reduce these costs over time to be closer to grocery stores.

Rider costs: This cost is net/new in the instant-delivery model compared to grocery stores. However, given the 1-mile radius and use of bikers and potential future batching of orders, it’s not infeasible for a driver to do 3-5 deliveries per hour. That would imply a cost of ~$4/delivery, or maybe ~15% cost of revenue assuming $25 average order values. That’s a lot of incremental costs, and suggests that they will likely need to add some convenience or delivery fee for at least small orders to sustain this in the future.

Based on this quick analysis, while it may be possible to get to profitability, it’s clear it will need these companies to be extremely efficient, and their margin structures are likely going to look a lot like grocery stores, and be somewhere in the 2-5% operating margin range at scale.

There are however some additional opportunities to grow margins slightly beyond that (or reduce the time to profitability) which I go into next.

D. The opportunity to grow margins

The instant-delivery apps have a few other opportunities to grow margins which can help them get to profitability sooner. Here are some of them:

Private Label Products

Some grocery stores such as Trader Joes are up to 80% private label products.

Since instant-delivery apps make a delta between the retail price of the product and the price they buy the products at, one obvious way for them to improve margins is to make some of the products themselves.

This only works at some sense of scale, but there are early signs that some are taking this approach, based on this job post by Fridge No More and this quote about Jokr from Sifted:

In the next two to three months, JOKR will also launch private label products, which traditionally have much higher margins for retailers. It will begin with food but could move into “any kind of product good — even up to cosmetics”. (via Sifted)

Ads and Discovery

While I talked about how the business models of these startups are quite different from the Doordash and Instacart type marketplaces, one commonality is that they can still grow revenue and margins by layering on ads as I’ve written about previously.

By showing promoted listings for specific products in the home feed or in search results, these companies can generate another revenue stream (the specific payment from the brand may come in the form of reduced costs on inventory, but the net result is the same).

In addition, a big benefit of these products is the local personalization that is possible, and the ability for them to allow for discovery of local brands and products.

This brand discovery element can be captured well through either a commission on transactions (or a lower cost) or more simply through promotional units.

It’s very possible certain brands give these instant-delivery apps a certain number of free samples of their product to get the name of the brand out in specific neighborhoods.

Automation and Fees

The cost of “picking” the order and delivering the order are two major cost drivers which these companies will be working to reduce over time.

There might be room for improved hardware and software to help reduce the first cost over time. While these fulfillment centers are small, since they aren’t designed for consumers, one could imagine the presence of more robots which can pick or fulfill parts of the order and reduce some of the labor costs (but incur some upfront costs). Now, they’re unlikely to be completely automated, but it may be possible to reduce the labor needed by 20-40%.

While the second one is likely to remain in the medium term since riders aren’t going away, two ways to reduce that cost are two increase operational efficiency and batch orders which may happen somewhat naturally as demand within neighborhoods increase and to play around with fees (add a fee for small orders but not if they’re fine waiting for 30 min etc.).

Closing Thoughts and Additional Reading

This space is very much in its infancy, with the current landgrab for market share taking place between a number of well capitalized competitors. Even DoorDash, Instacart, Uber and Amazon are experimenting with some versions of this model and while the joke about “Webvan and Kozmo tried this in 1999 and look what happened” will continue, the reality is a lot has changed about consumer demand and expectations as well as operations know-how and software since then which does make it more feasible now.

But it will be interesting to see how this pans out and one thing to keep an eye in the short term is how long the current no-fee no-order minimums and lots of promo codes approach sustains before a potential paring back and move towards profitability at least in mature markets.

Here are a few additional reads on this phenomenon.

Sifted’s Essay on Gorillas

GroceryDive’s Interview with 15/20’s Co-founder

Turner Novak’s Essay on Jokr and Instant Commerce

The Information on Instant Delivery Startup’s Losses

GroceryDive piece on DoorDash’s plans with Dark Stores

Thanks for reading! If you liked this post, give it a heart up above to help others find it or share it with your friends.

If you have any comments or thoughts, feel free to tweet at me.

If you’re not a subscriber, you can subscribe below. I write about things related to technology and business once a week on Mondays.