The rise of intangibles and the demise of accounting

One of the big shifts in the economy has been the rise of intangible assets such as software, data, customer franchises and so on, which now make up a bulk of enterprise value.

While the world has changed, accounting standards have not, which in my view has made income statements and balance sheets less relevant.

Today I’ll cover this rise of intangibles and how it has made accounting less relevant.

The rise of intangibles

Back in the day, a majority of most companies’ value stemmed from tangible assets. These were things like plants, machinery, raw materials, and so on, which were then transformed into finished products and sold and thereby converted into revenue.

These assets sat on the balance sheet, and so the balance sheet was a good representation of the assets that a company had amassed at any given point in time.

In today’s age, especially with technology companies, “intangible” assets have taken center stage and are the key driver of company value. Think intellectual property such as patents and trademarks, software and data, customer franchises, and even goodwill and brands.

As the chart below shows, intangible assets have gone from making up 14% of the S&Ps enterprise value in 1975 to now representing over 84%!

Today, for most of the largest companies the majority of their value comes from intangible assets. Is this trend going to continue? The answer is a resounding yes.

As the graph below shows, investment in intangibles crossed the investment in tangible assets in the mid-90s. Since then, the investment in intangibles and the delta has continued to increase.

Accounting’s Job To Be Done

So how does this impact Accounting? First, let’s quickly touch on what the goal of accounting is.

John Collison described the jobs to be done of accounting in his podcast with Patrick O’Shaughnessy as below:

We're actually trying to do a number of different jobs with accounting.

We're trying to figure out how much profit we are in so we know how much tax we have to pay. That's one job we have. We're also trying to help the business run itself. We're trying to broad a view of the business managers so that we can determine whether we need to invest in new machinery to be more efficient or something like that. We're also trying to solve for the needs of creditors, where people want to be able to evaluate the business and understand, really to enough money to pay off its debt. And then we're also separately, importantly, trying to solve for the needs of equity holders, where they're trying to understand what are the long-term cash flows for this business going to be.

And the reason I bring that up is people think of accounting and GAAP as these fundamentals that are etched into stone tablets. I mean, accounting standards are invented by us humans to give us a view of a business. And they're up to us to choose.

We can synthesize the overall JTBD of accounting as getting a better sense of the current state of the business and the ability to predict the future state (and cash flows of the business).

Intangibles and Accounting

So what’s the big deal about the rise of intangibles? The big deal is that the rise of intangibles has made accounting less relevant.

A 40-year accounting rule, SFAS No. 2 1974, which came into existence essentially prior to technology as we know it, requires that R&D be expensed.

“This Statement establishes standards of financial accounting and reporting for research and development (R&D) costs. This Statement requires that R&D costs be charged to expense when incurred. It also requires a company to disclose in its financial statements the amount of R&D that it charges to expense.”

And it’s not just R&D - investments in other intangibles such as brand, goodwill, customer franchises, unique processes, etc get expensed immediately, rather than being capitalized (and so don’t show up as assets on balance sheets)

By expensing them immediately, we’re essentially saying that they have no value in the future. But in reality, this investment leads to the creation of an asset that has value in the future.

So back to our goal with accounting: It’s to better understand a business for which we often use the income statement and the balance sheet to ascertain profitability and ability to generate profit in the future. But with the rise of intangibles given today’s accounting standards, both the income statement and the balance sheet are losing relevance.

Take two companies O and N. O is an “Old Economy company”, which invests $10M in a factory with machinery to produce physical widgets which it sells. It believes that the factory has a useful life of 10 years, and so depreciates the value of the factory by $1M each year. So in year 1, the impact on earnings of this investment is $1M expense, and $9M sits on the balance sheet.

Now take company N which is a “New Economy company”. It invests $10M in R&D to create software. This software will continue to be useful in the future, but per GAAP accounting, it will expense all of the $10M this year. So in year 1, the impact on earnings of this investment is a $10M expense, and the balance sheet reflects nothing. In addition, let’s say they spend $10M to acquire recurring revenue customers. They will earn revenue from these customers for many years in the future, but many of the costs are expensed immediately. In addition, their customer base has grown which will lead to recurring revenue in the future doesn’t show up on their balance sheet.

Two things stand out from this toy example:

Earnings can basically become meaningless when companies are investing in growth. Companies are being penalized in that their expenses are not being matched to the revenues. While they will continue to earn revenue from a software or a customer in the future, the expense the cost to build it or acquire that customer immediately. This artificially deflates earnings.

The balance sheet isn’t really reflecting all the assets that a company has built up and so can also be somewhat meaningless because many key intangible assets that result in the creation of these intangible assets are not showing up on it.

Understanding the impact on earnings

Now that we’re done with our toy example, let’s look at a few big buckets of spend and understand the impact of treating intangibles this way.

For simplicity, I’ll use a median SaaS company in this example, but it’s easy to see how the following apply to other industries such as pharma/biotech, tech, media, or CPG.

Below is a summary of some of the kind of assets that investments in these areas of spend may create (and why they potentially should be capitalized).

For each of these categories, knowing or estimating two things is key:

What percent of the spend is an intangible investment (vs say just a maintenance expense for the year)

What is the useful life of the intangible investment (i.e., how many years do we amortize that investment over)

R&D spend

Perhaps the most obvious form of intangible investment is that of R&D. R&D is for new economy companies what purchasing PPE is for the old ones, but the latter gets capitalized and the former doesn’t.

R&D typically represents all the costs related to research and development into R&D. While some of it may be maintenance spend (“R&D” to keep the lights on) the benefit of which is used up in the period, a large chunk of it tends to be R&D going towards developing software or data, the benefits of which go much beyond that year in which the R&D is spent.

The median SaaS company spends ~23% of Revenue on R&D. Today, all of that gets expensed every year. But let’s say that 20% of that R&D spend is some form of maintenance R&D, and the remaining 80% is used to develop new software that is useful to the company beyond that year.

What’s the useful life of it? While it’s hard to know exactly (unlike for something like patents that have a clearly defined period), we can use 5 years as a starting point.

So what happens if we expense and amortize R&D as such relative to expensing all of it immediately? We get higher earnings for a growing company, implying that the current method understates earnings for a growing company, as illustrated in the example below by 8-10%.

S&M spend

The median SaaS company spends ~45% of revenue on Sales and Marketing each year.

Now, this includes a whole lot of things such as advertising spend, salaries and overhead on marketing and sales personnel, sales commissions, and so on. And while some of these things are rightly expensed over time such as sales commissions, many others are expensed immediately. Probably the easiest example of this is incentives, free pilots, and other work done which typically goes into “customer acquisition cost”.

For a growing company, while the sales and marketing expense looks huge because of the amount being spent to grow customers, what often gets ignored is that once acquired these customers bring in recurring revenue for years to come, and the company is building a vital “customer franchise” asset.

So let’s say 1/3 of the spend is maintenance / non-investment and should be expensed immediately, and the other 2/3s is an investment in intangibles. And let us amortize the intangibles over a 3 year period.

Again, the impact of this is that earnings could be understated for a growing company that is spending a constant % of revenue on sales and marketing. The exact amount will depend on the amortization period and the growth in marketing spend and in this example is understated by 5-10%.

G&A spend

G&A spend is both a smaller bucket and tends to involve less “investments”, but its worth touching on quickly.

The median SaaS company spends ~16% of revenue on G&A. G&A includes administrative costing and spend including office leases and so on which are properly expensed, but also includes investments in workforce development and training which tend to have benefits beyond the year.

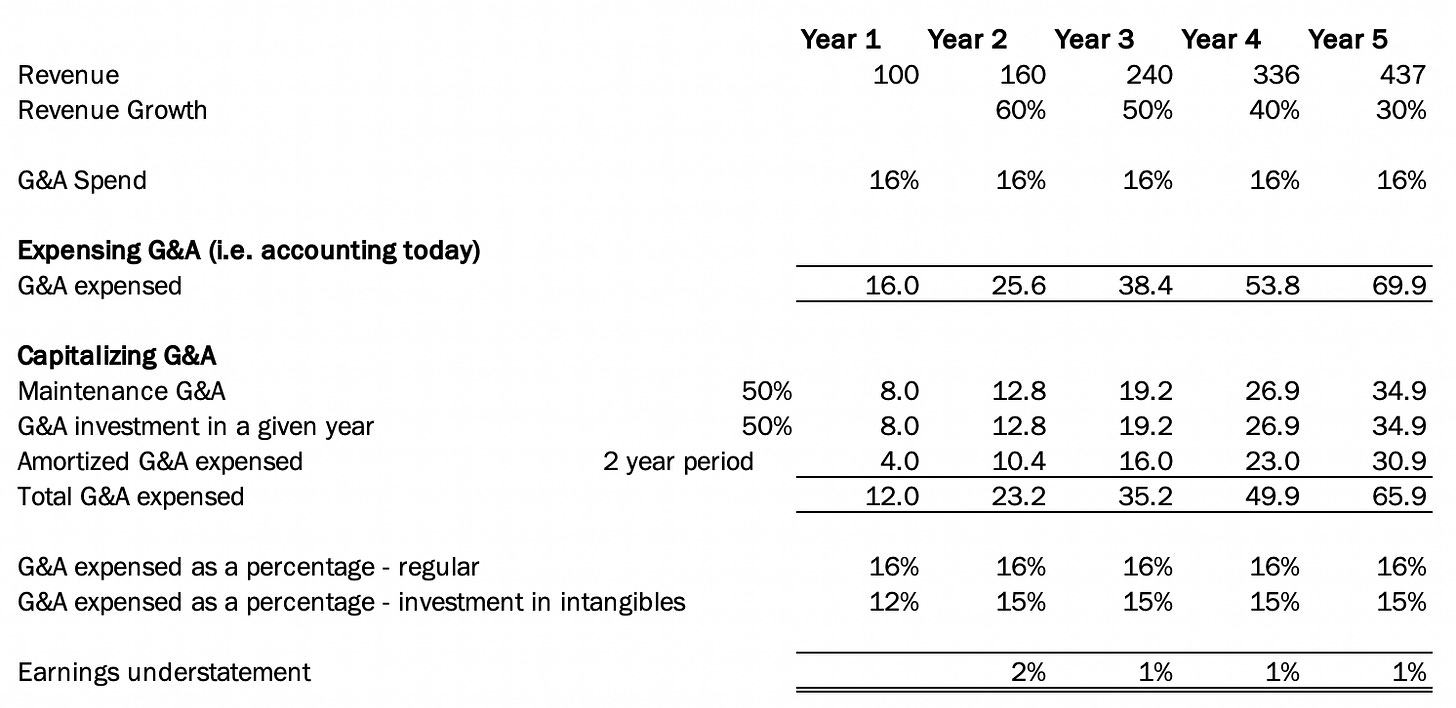

Let’s say that 50% of G&A is maintenance / non-investment G&A and that the remaining 50% should be capitalized over two years.

Here’s what these assumptions lead to in a growing company where G&A spend (as a percentage of revenue) is constant - earnings are understated by 1-2%.

Combining the above, it’s very possible that the real earnings and margins of a growing company are ~15-20% higher than reported due to this accounting difference, though the exact numbers depend on how much they are investing in each of these areas and how valuable these investments remain over time.

Not only does this accounting for intangibles make the reported profitability meaningless, but it also could inflate or deflate ROE and ROA ratios. While the exact impact of the adjustment could be in either direction since both the numerator and denominator increase (numerator is higher since we have higher profitability in a given accounting period and the denominator is higher since we have more assets and higher earnings retained).

Closing Thoughts

The world has changed a lot and unfortunately, some of the accounting standards haven’t kept up.

Companies may still need to comply with GAAP earnings for now, but anyone who wants to better understand new world companies, whether it be internally or externally, should think about how a company is investing in intangibles and what intangible assets they are generating and have generated.

One of the good things about free cash flows is that they are unaffected by the adjustments described above, and so remain a good proxy for company performance.

But to understand the ability to generate free cash flows in the future, one should not rely on current earnings or balance sheets, since they may not reflect the reality for a lot of companies.

In closing, it’s also interesting to consider that when companies acquire other companies, they can capitalize some of the assets such as brand and goodwill, but they can’t if they generate those assets through internal investment.

Further Reading

If you’re interested in going deeper in this topic, here are a few interesting reads.

The book The End of Accounting by Baruch Lev and Feng Gu

Brand Finance’s Global Intangible Finance Tracker

Invest Like the Best podcast with John Collison

Raconteur’s Valuing Intangibles infographic

Thanks for reading! If you liked this post, give it a heart up above to help others find it or share it with your friends.

If you have any comments or thoughts, feel free to tweet at me.

If you’re not a subscriber, you can subscribe below. I generally post once a week or every other week on Monday about things related to technology or business.

Just my two-cents. If we refer to the IFRS:

Initial recognition: research and development costs

Charge all research cost to expense. [IAS 38.54] Development costs are capitalised only after technical and commercial feasibility of the asset for sale or use have been established. This means that the entity must intend and be able to complete the intangible asset and either use it or sell it and be able to demonstrate how the asset will generate future economic benefits. [IAS 38.57]

As shown above, R&D costs could be capitalized as long as they are feasible for use or sale. The company just needs to demonstrate this.

For goodwill, sometimes it’s quite difficult to reliably measure the value of internally generated goodwill. A different matter for goodwill acquired in a business combination as we could use the transaction price.

As for customer acquisition costs, costs incurred related to contracts to those customers could be capitalized based on IFRS 15.

I was really hoping to read something insightful but instead, all I got from the first 3 pages or so were basically baby arguments. Not to mention the errors abound within the literature. One needs to understand the standard setting processes and also financial history and the impact of frauds on the global economy before delving into such issues as the relevancy of standards and financial statements. For correction on one or perhaps two things you spoke of, 1) software costs are capitalized once technological feasibility is achieved., 2) SFAS 2 was replaced and incorporated into another SFAS, I believe it was either SFAS 5 or 8.

Also, FASB adopts a conservative approach in reporting financial transactions as a fundamental concept. This concept helps both the SEC and FASB to keep control on scrupulous entities and prevent them from misleading and defrauding investors.