Customer Concentration Risk in B2B Tech Companies

Hi friends,

This week I’ll be touching on the idea of concentration risk in fintech and infrastructure B2B / B2B2C companies. We’ve seen many such companies recently go public where they’ve had a glaringly high percent of their revenue come from a few customers, which is usually seen as a big risk.

But sometimes, it’s not as big a risk as it seems, which is what I’ll go deeper into.

Customer Concentration in Fintech / B2B infra

B2B Fintech is filled with examples of high customer concentration risk. Generally, companies are required to disclose their customer concentration, especially if one customer accounts for over 10% of revenue.

When Affirm went public, Peloton was their single largest merchant, representing ~30% of their revenue.

When Marqeta went public, Square was their single largest customer, representing ~70% of their revenue

When Greendot went public back in 2010, Walmart was their single largest customer, representing ~63% of their revenue

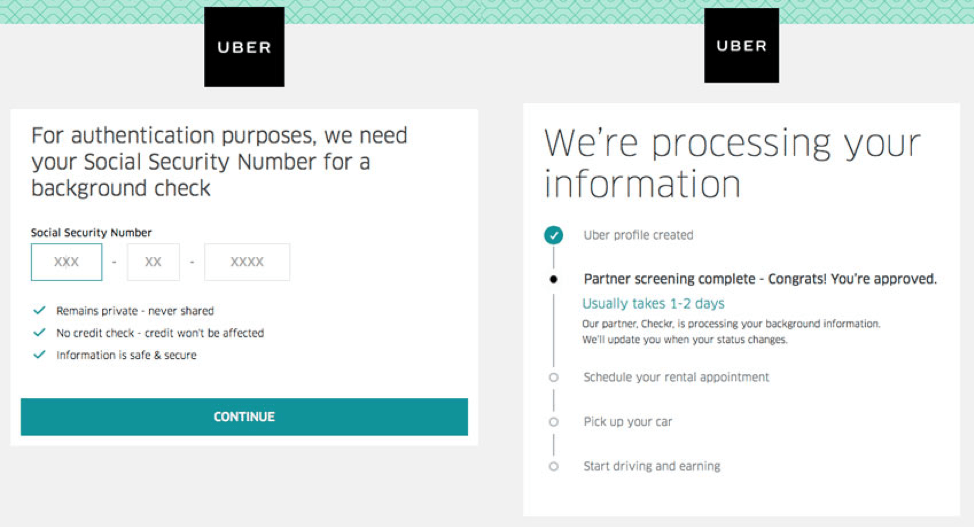

Checkr famously had Uber as a flagship customer in its early days, with Uber representing a majority of its revenue in its first few years.

Why concentration is typically a risk

The typical view (and rightly so) across all businesses is that customer concentration poses a risk for the following reasons:

The loss of a few customers can have an extremely outsized impact on revenue and an even bigger one on profits and cash flow.

The large customers potentially hold the upper hand when it comes to negotiations and can probably extract more value out of the business.

Businesses may have to disproportionately cater to these large customers at the cost of serving the needs of smaller customers. This also ironically sometimes makes it harder to diversify the risk away since existing resources are often catering to serving these large customers.

So, it’s not surprising that typically highly concentrated businesses are viewed less favorably by lenders, potential acquirers, and even public markets in the multiples they command.

The positives of concentration

Now, let’s talk about some situations where concentration risk can be a positive sign for fintech and B2B infra type companies.

A. Concentration as a sign of product market fit

Especially early on, concentration is just an indication you’ve found a hero customer and have a value proposition nailed down. As you grow customers and if the hero customer remains a large share of revenue, it’s usually a sign you’re providing something valuable which they would rather leave to you to do than figure out themselves.

In the case of Checkr, the high concentration from Uber actually indicated product market fit and a clear value proposition. If even the largest companies who needed to perform background checks were willing to use a 3p provider rather than build themselves, it’s a good sign they were onto a real business which solves the needs for a lot of companies. Checkr was able to expand over time to customers such as Adecco, Instacart and Lyft.

B. Concentration as a sign of ability to grow with large customers and capture value from that growth

If concentration comes as result of landing a large customer and then them significantly expanding their usage over time, that generally indicates that:

the product solves a real problem

that the pricing model is efficiently capturing value from their increased usage (typically in the form of usage-based pricing)

that the customer is happy with the business thus far as its continued to scale with them

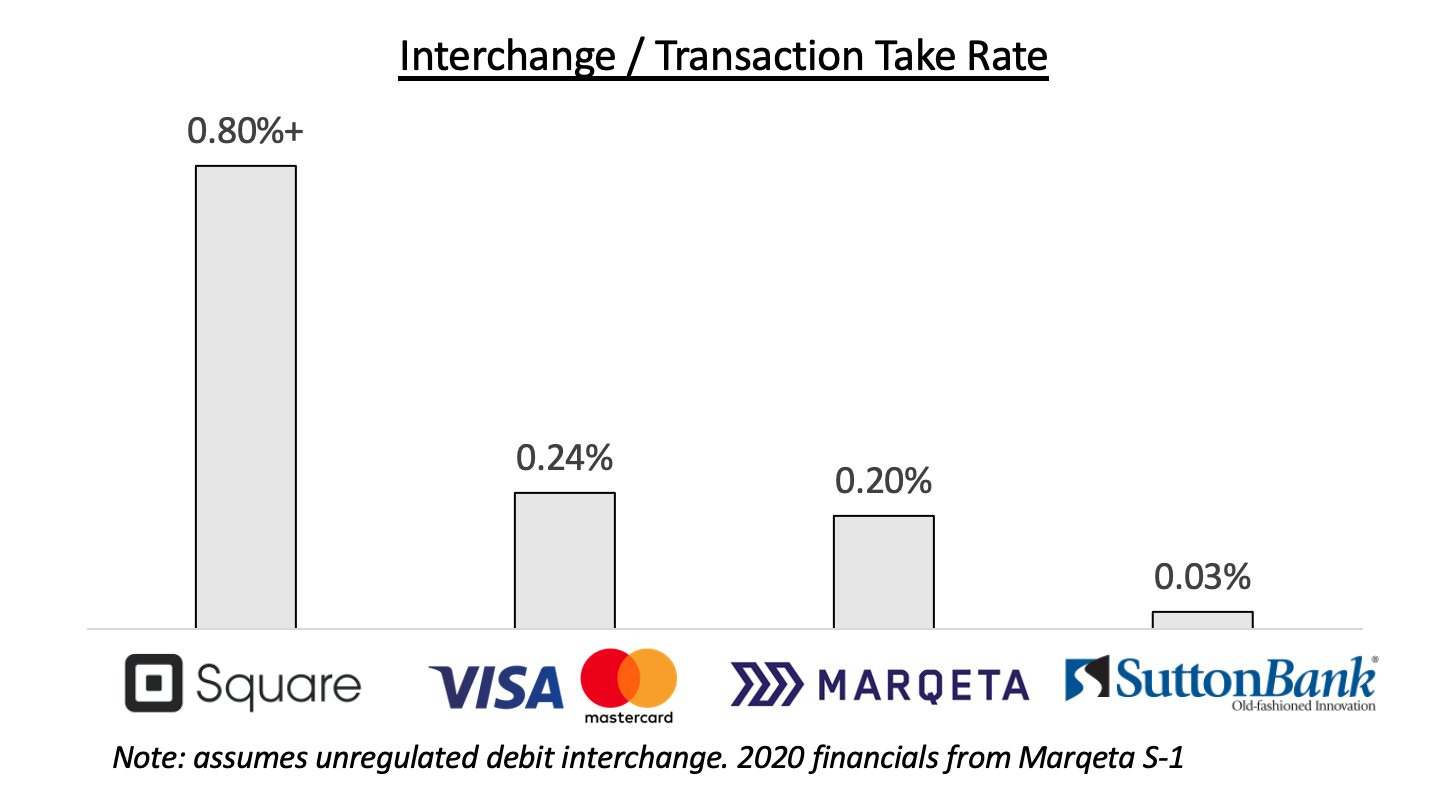

A great example of this is Marqeta, which signed Square in 2017, and then the TPV processed by Square really grew over time. However, since Marqeta makes a percentage of TPV, this also meant their revenue from Square grew over time. In addition, Square deepened their relationship with Marqeta over time, using them for the Cash App card on the consumer side, and the Square Card on the merchant side.

If you don’t yet receive Tanay's newsletter in your email inbox, please join the 3,000+ subscribers who do:

C. Concentration as a leading indicator of ability to scale to other large customers

As mentioned above, concentration in some sense shows that the business has been able to scale well with a specific large customer, and that the customer has chosen to stick with them rather than building inhouse.

Consider that one customer using a business a lot, especially a large and important customer, could be a leading indicator that a lot of other large and important customers may want to use the business’s product and can rely on the business.

In that sense, concentration risk at a moment in time, may just indicate an ability to attract and scale to other large customers.

Probably the best example of this is Affirm. Much was written about how Peloton accounted for ~30% of its revenue at IPO.

However, Affirm was soon able to partner with even larger customers, and now has partnerships with:

Amazon: ~$600B in GMV

Shopify: ~$170B in GMV

Target: ~$90B in GMV

Walmart eCom: ~$70B in GMV

Compare that to Peloton which is <$3.5B in sales.

It’s the not a surprise that Affirm essentially was able to remove that concentration risk from Peloton in ~12 months, as per their latest quarterly earnings:

Peloton’s concentration declined to 8% of our GMV this quarter compared to 29% in the year-ago quarter

One can view Peloton as a leading indicator of Affirm’s ability to attract to other large customers, rather than a risk that their business depends on Peloton.

Mitigating concentration risk

Additionally, there are some situations where even though a customer may represent a large share of revenue, the concentration risk is reduced or some ways in which companies with high customer concentration can mitigate the risk somewhat.

A. Long term contracts

One way some of these businesses reduce the customer concentration risk is by trying to lock up the customers into longer term contracts in exchange for favorable rates.

For example:

As of 2021, Marqeta had their agreement with Square for Square Card until December 2024 and for Cash App until March 2024 with each agreement automatically renewing for successive one-year periods beyond that.

Similarly, for Affirm, they entered into a renewed merchant agreement with Peloton with an initial three-year term ending in September 2023, which automatically renews for additional and successive one-year terms until terminated.

B. Aligning long-term incentives via equity grants

Another way companies can mitigate the customer concentration risk is by providing strategy and large customers with equity grants which should defray them from switching to another competitor and better align long term incentives.

Marqeta has given options in Marqeta to a few customers:

Square has warrants of 1.1M shares (worth ~$40M at IPO)

Uber has warrants of 750K shares (worth ~$26M at IPO)

Ramp has warrants of 50K shares (worth ~$2M at IPO)

Similarly, Affirm has been doing the same.

Shopify was granted 20M penny warrants of Affirm when they entered into a partnership

Amazon was granted an initial grant of 1M penny warrants and an additional 6 million that vest over the initial 3-year duration of their contract with Affirm.

C. Complex Product sharing Economies of Scale

When a customer representing a high share of revenue leaves a fintech / infra business, it is typically because it has decided to:

Either build out the product internally given rising spend

Or switch to a competitor

Typically, these become more unlikely if:

The product is very complex replace because of regulatory burden and partnerships

The product is costly to replicate

The business has some kind of economies / benefits of scale, which it is sharing with the customers.

The function that the business solves is not core or in the wheelhouse of its concentrated customers

There are a lack of at-scale competitors to the business

As an example of the benefits of scale point: As Marqeta grows it is able to negotiate better fees with card networks which increases the net interchange rate that can be shared between Marqeta and its customers (Square) over time. If its sharing some of these gains with its customers, it’s possible that customers will always feel like they’re better off staying with Marqeta.

If customers were to try to replace Marqeta by building internally, it may end up earning not that much of a higher interchange than what Marqeta can provide them, because they would end up paying more to the card networks and the banks (let alone the costs to build / form partnerships).

Thanks for reading! If you liked this post, give it a heart up above to help others find it or share it with your friends.

If you have any comments or thoughts, feel free to tweet at me.

If you’re not a subscriber, you can subscribe below. I write about things related to technology and business once a week on Mondays.